Introduction

In every digital communication, two fundamental questions arise:

- Who am I talking to?

- How do I ensure no one else can read or alter what we say?

These questions define the core problems of authentication and encryption. Without a trusted way to answer them, any network is vulnerable to impersonation, eavesdropping, or tampering.

The Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol was designed to solve these problems. It ensures that two parties, such as a browser and a web server, or a VPN client and endpoint can establish a secure and trusted communication channel over an untrusted network. However, in most common cases like HTTPS, only the server is authenticated. The client trusts the server’s certificate, but the server doesn’t know who the client really is.

This is where Mutual Authentication (or Mutual TLS, mTLS) comes in. Unlike one-way TLS, mutual authentication verifies both sides. The client proves its identity to the server, and the server proves its identity to the client. This two-way trust is built on the foundation of Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) — a system of digital certificates, public and private keys, and trusted authorities known as Certificate Authorities (CA).

Understanding PKI and how TLS uses it to create secure sessions is essential before diving into implementation details like VPN connections secured with mutual TLS.

In this article, we’ll break down the building blocks:

- Why public and private keys are used

- The role of Certificate Authorities

- How symmetric and asymmetric encryption work together

- And how certificates enable passwordless identity verification in mutual authentication.

TLS vs SSL: Clearing the Confusion

Before we dive deeper into Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) Explained, it’s worth clarifying a common misconception: TLS and SSL are not the same thing.

SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) was the original encryption protocol developed by Netscape in the 1990s. It secured early web traffic but contained several design flaws that made it vulnerable to modern attacks. As a result, SSL was replaced by TLS (Transport Layer Security) — a standardized, stronger, and more efficient protocol.

TLS inherited the core idea of SSL (encrypting and authenticating network connections) but fixed its weaknesses. Every modern “SSL certificate” you see today is technically a TLS certificate

In short: SSL is obsolete, TLS is the real standard.

Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) Explained

As a big fan of Harry Potter, I’d like to explain how Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) works through a story from the wizarding world. It’s easier (and a bit more fun) to understand encryption, digital signatures, and trust if you imagine Harry, Ginny, and a certain troublemaker named Malfoy.

The Secret Letter: Symmetric Encryption

Harry writes a love letter to Ginny and wants to make sure nobody else can read it. He decides to encrypt the letter before sending it. The simplest way is to use a symmetric key, one secret key that can both encrypt and decrypt. But there’s a problem:

How can Harry give this secret key to Ginny securely, without anyone else (like Malfoy) intercepting it?

If he sends the key openly, Malfoy could copy it and read the letter too. Harry needs a way to exchange the key safely, and that’s where asymmetric encryption comes in.

Exchanging Keys: Asymmetric Encryption

Instead of sharing one secret key, Ginny creates a key pair: a private key that she keeps secret, and a public key that she can safely share with anyone. The two keys are mathematically related. A message encrypted with one key can only be decrypted with the other.

If Harry encrypts something using Ginny’s public key, only Ginny can decrypt it using her private key.

Likewise, if Ginny encrypts or signs something using her private key, anyone with her public key can verify it.

Because the public key is not secret, it can be exchanged openly between Harry and Ginny, even over an insecure channel. No one can use the public key alone to read encrypted messages or to impersonate Ginny, since the private key never leaves her possession.

Now Harry can encrypt the symmetric key using Ginny’s public key. Once encrypted, only Ginny can decrypt it with her private key. This guarantees that only Ginny, and no one else, can open Harry’s message.

At this point, the letter is private. But Ginny still doesn’t know who actually sent it.

Proving Identity: Digital Signatures

To prove that the letter truly comes from him, Harry digitally signs it.

He first creates a hash of the letter. A hash is a one-way mathematical function that produces a short, unique fingerprint of the data. It’s called “one-way” because you can’t reverse the hash to recover the original message. If even a single character in the letter changes, the resulting hash will be completely different.

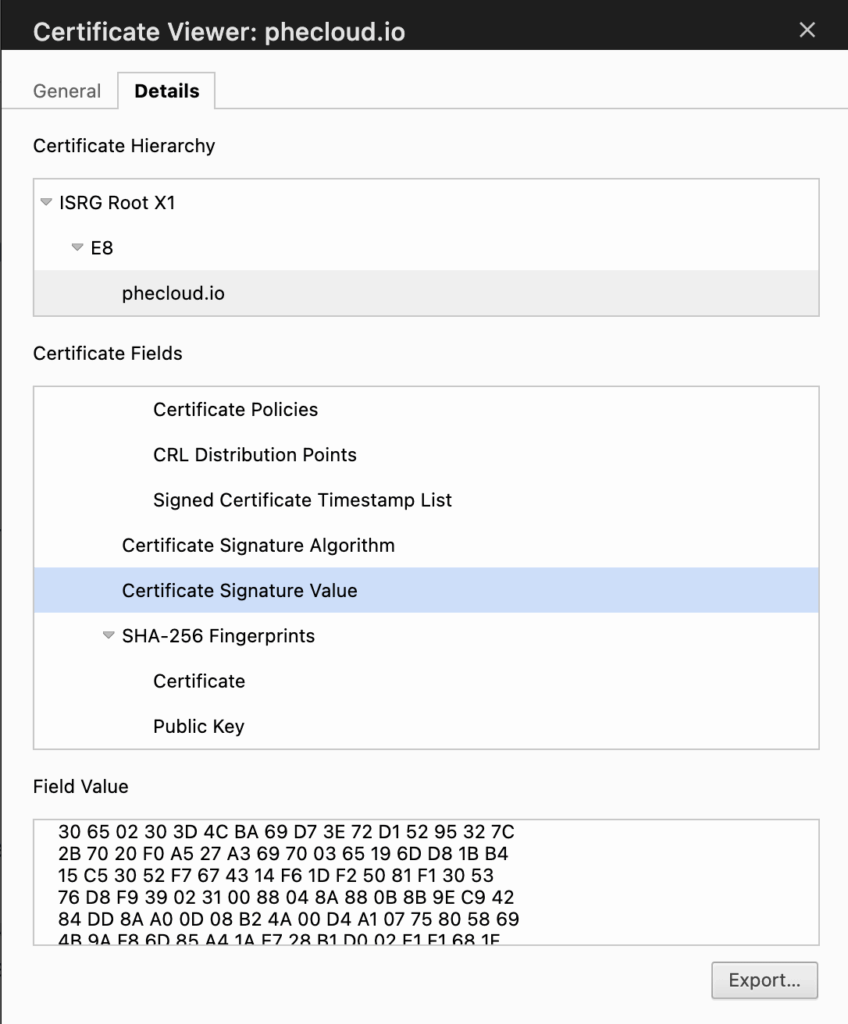

Harry then encrypts that hash using his private key. This encrypted hash is the digital signature.

When Ginny receives the letter and the signature:

- She decrypts the signature using Harry’s public key to recover the hash.

- She computes the hash of the received letter herself.

- If both hashes match, she knows two things:

- The letter hasn’t been altered (integrity).

- It truly came from someone holding Harry’s private key (authenticity).

That’s the essence of digital signing: proving identity and integrity without sharing any secret.

The Problem of Trust: Enter Malfoy

Now, what if Malfoy intercepts the message?

He could read the letter, replace it with his own fake one, sign it with his own private key, and send Ginny a fake public key pretending to be Harry’s. Ginny would verify the fake letter successfully, because she’s using Malfoy’s fake key. The problem isn’t the encryption, it’s trust. She has no way to know whether that public key really belongs to Harry.

Solving Trust: The Role of the Certificate Authority (CA)

To solve this, the wizarding world establishes a trusted agency, like a magical Ministry of Identity, called the Certificate Authority (CA).

When Harry generates his public key, he sends it to the CA along with proof of his identity.

The CA verifies that Harry is truly Harry, then issues him a digital certificate.

This certificate contains:

- His identity information (like a name or domain)

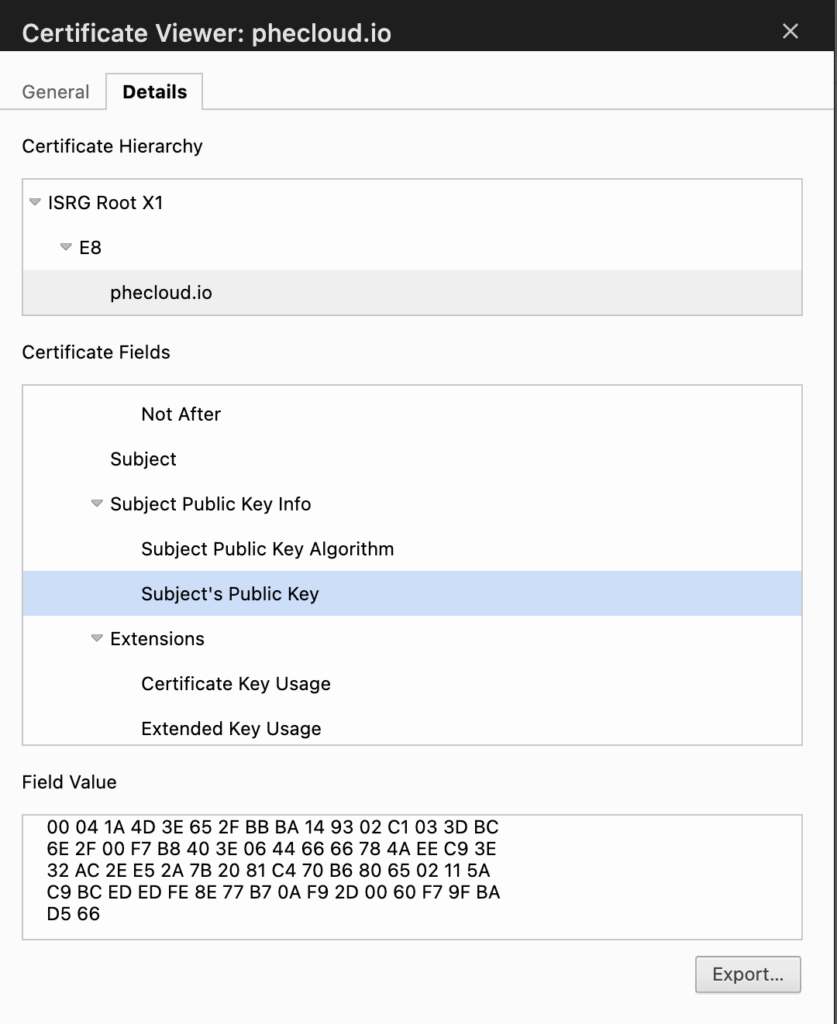

- Harry’s public key

- And the CA’s digital signature confirming that the key indeed belongs to him.

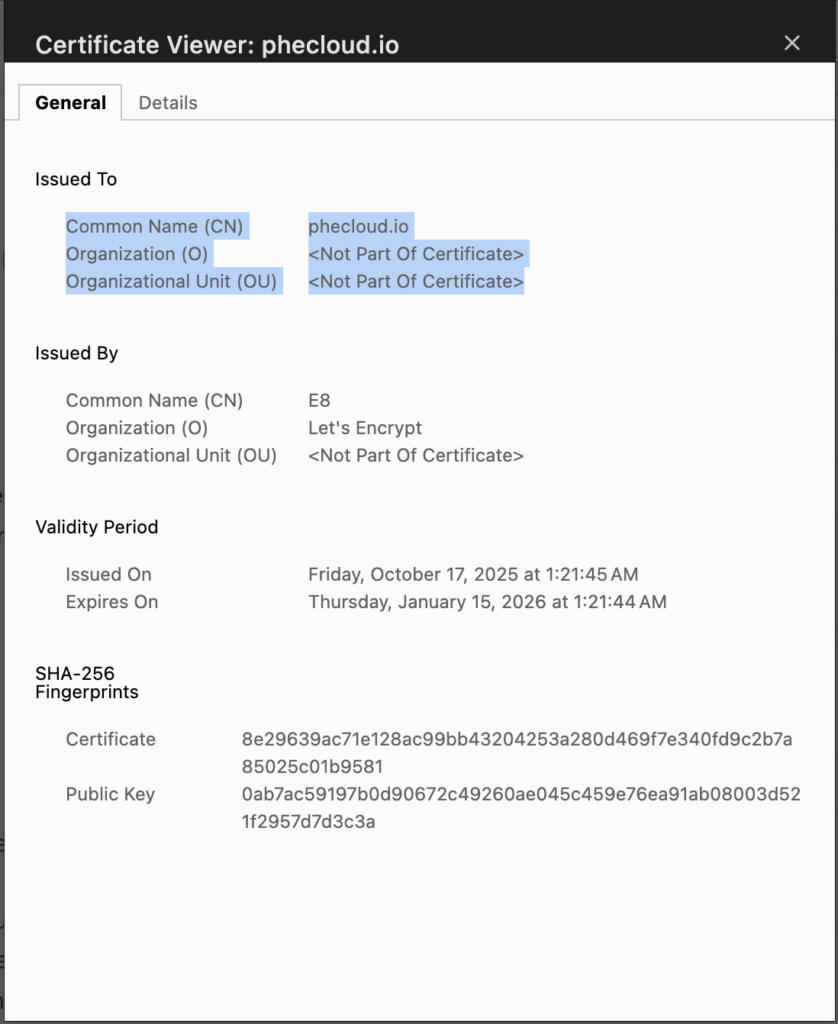

for example:

When Ginny receives Harry’s letter and certificate:

- She verifies the CA’s signature using the CA’s public key.

The CA’s public key is not secret; it’s distributed globally and pre-installed in all major operating systems and browsers on the market. This is why her system already trusts the CA without having to contact it directly. - If the signature is valid, she can trust that the certificate, and therefore the public key, really belongs to Harry.

Even if Malfoy tries to fake a new key, Ginny’s system will reject it because it won’t carry a valid CA signature.

From Letters to the Internet

This story is exactly how the Internet works today. Every secure connection, whether it’s a browser visiting a HTTPs website or a client connecting to a VPN, follows the same principles:

- Symmetric encryption for data privacy (fast and efficient).

- Asymmetric encryption for secure key exchange and identity verification.

- Digital signatures to prove authenticity and prevent tampering.

- Certificate Authorities (CA) to ensure public keys truly belong to the identities they claim.

In short, PKI is the invisible trust fabric of the Internet.

It turns ordinary keys into verified, trustworthy digital identities.

How Mutual Authentication Works (mTLS)

In the previous section, we saw how certificates and digital signatures solve the problem of identity and trust. Now let’s see how these concepts are applied in practice through mutual TLS (mTLS), the protocol that allows two parties to verify each other before exchanging encrypted data.

One-way TLS vs Mutual TLS

In a typical HTTPS connection, only the server presents a certificate. The client verifies that certificate using a trusted Certificate Authority (CA) and then establishes an encrypted session. This is known as one-way TLS because only the server’s identity is authenticated.

Mutual TLS (mTLS) takes this one step further. Here, both sides exchange certificates and prove possession of their private keys. Each certificate is issued and signed by a Certificate Authority (CA) that the other party trusts. In real systems, the client and server may use different CAs, as long as each side can verify the other’s certificate chain.

In our Harry and Ginny example, both rely on the same Ministry of Magic, their shared CA, which acts as the single root of trust that validates their identities. The server proves that it is genuine through its CA-signed certificate, and the client proves that it is an authorized user or device using its own certificate signed by the same CA. This two-way validation ensures that both sides can trust each other before any data is exchanged, effectively preventing impersonation or unauthorized access.

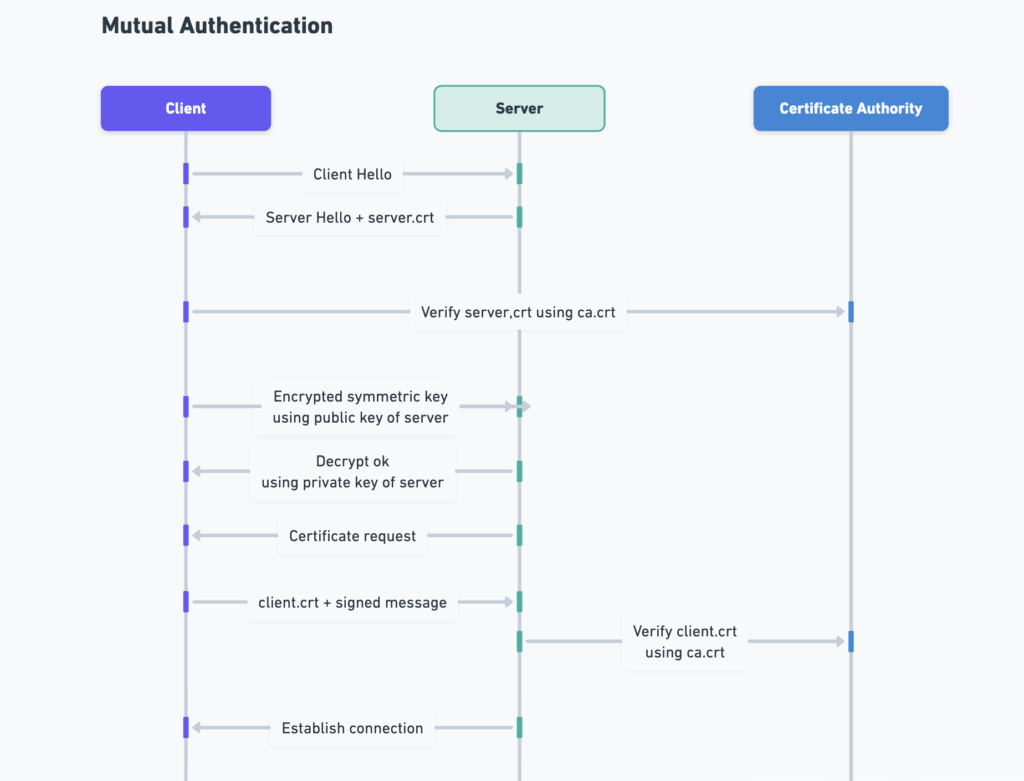

The Handshake Flow

The mTLS handshake follows the same logic you saw in the Harry and Ginny story. Both sides use certificates to verify identity, digital signatures to prove ownership of private keys, and asymmetric encryption to establish a symmetric session key for data encryption.

The process looks like this:

- Client Hello / Server Hello

The client starts the handshake by sending a greeting message, listing supported encryption algorithms. The server replies with its chosen parameters and sends its server certificate (server.crt). - Server Authentication

The client verifies the server’s certificate using its trusted CA certificate (ca.crt), just as Ginny verified Harry’s identity through the Ministry of Magic (the CA). The client then extracts the server’s public key from the certificate. - Secure Key Exchange

The client generates a symmetric session key, encrypts it using the server’s public key, and sends it over. Only the server can decrypt this information with its private key, ensuring that no one else can access the key. Both parties now share the same symmetric key, which will be used for fast, encrypted communication (for example, AES). - Client Authentication

The server now asks the client to present its own certificate (client.crt). The client sends this certificate along with a digital signature created using its private key. The server verifies this signature using the public key inside the client’s certificate and confirms that it was signed by the same CA. - Session Established

Once both verifications succeed, the TLS handshake completes. Both sides have proven who they are, exchanged a shared session key, and established an encrypted channel that only they can read.

At this point, both the server and client can communicate securely and confidently, just as Harry and Ginny could exchange letters without Malfoy being able to read or forge them.

Notes

- Verification does not involve contacting the CA server

In the handshake diagram, you may see verification arrows pointing to the CA, but in practice, neither the client nor the server actually sends a request to the CA. The CA’s public certificate (which contains its public key) is already stored locally on both systems as part of their trusted certificate store. This allows them to verify digital signatures instantly and offline, without any network communication with the CA. - Client authentication is omitted in HTTPS

In one-way TLS (as used in HTTPS), the handshake ends after the server authentication step.

The server is authenticated using its certificate, but the client is not. The client’s browser simply verifies the server’s identity and then establishes an encrypted session. This design keeps HTTPS simple and scalable for billions of users, since clients do not need to maintain personal certificates.

Why mTLS is Passwordless Authentication

Mutual TLS eliminates the need for passwords altogether. Instead of asking the user to type a credential that could be guessed, stolen, or phished, the client simply proves ownership of a private key.

The client’s digital certificate is tied to its unique key pair. During the handshake, the client signs a message with its private key, and the server verifies the signature with the corresponding public key.

If the verification succeeds, the server knows the client is genuine without ever transmitting a secret.

This makes mTLS a secure form of passwordless authentication. It relies on cryptographic proof rather than shared secrets.

Because the private key never leaves the client’s device and cannot be guessed or duplicated, mTLS provides both strong authentication and end-to-end encryption in one protocol.

In short, mTLS applies the same trust model that we explored in PKI, turning theory into a real-world handshake.

It ensures that both sides of a connection can prove who they are before sharing any encrypted data.

Why Mutual Authentication Is Not Common in HTTPS

Although mutual TLS offers stronger security, it is rarely used on the public web. The reason lies in scalability and usability. Mutual TLS requires every client to have a personal certificate issued and managed by a trusted Certificate Authority (CA). This means that every user would need to generate a key pair, protect their private key, request a certificate, and install it in their browser. Managing certificates for millions or billions of Internet users would be logistically impossible and extremely expensive.

By contrast, one-way TLS only requires the server to present a certificate. The client (browser) already has a built-in list of trusted root CAs, so it can automatically verify any legitimate website without additional setup. This model strikes a practical balance between security and convenience, which is why HTTPS has become universal.

In practice, user authentication on the web is handled at a higher layer of the stack, above TLS.

Instead of relying on certificates for every client, websites typically use simpler and more flexible mechanisms such as username and password, multi-factor authentication (MFA), OAuth tokens, or SSO (Single Sign-On). These methods operate after the TLS handshake has already established a secure channel, providing identity verification without the complexity of certificate management.

Mutual TLS, on the other hand, remains common in closed environments such as enterprise networks, internal APIs, and VPNs, where both clients and servers are under centralized administrative control and certificate management can be automated.

What’s Next

Now that we understand how mutual authentication works and how PKI provides the trust foundation behind it, the next step is to see how these concepts come together in practice.

In the next article, we will build a secure AWS Client VPN that uses mutual certificate-based authentication. We will generate our own CA using OpenSSL, issue server and client certificates, upload them to AWS, and verify how both sides authenticate each other during the VPN connection.

That practical guide will demonstrate how the theory of PKI, certificates, and TLS handshake comes to life inside an AWS networking setup.